An Oxymoron’s Guide to Sustainable Travel by Calvin Grover

Posted on

01/23/23

Author

Alex Biddle

This blog was first published on theyakboard.com by Calvin Grover – a Princeton Novogratz Bridge Year participant in Indonesia.

“Front wheels are off the ground… Back wheels! We’re flying!!!” My brother and I pulled invisible yokes and pushed imaginary throttles to complete the takeoff, leaning over one another to peer through the window at the receding tarmac with the naive wonder of children. For as long as I can remember, my brother and I were obsessed with the miracle of flight. Vacations were better the further away they were, especially when we needed more than one plane to get there, as that way we had higher chances of getting window seats. These days when I look through the plexiglass of an airplane window, I am still struck with childlike awe at the power of aeronautical engineering, but now that nostalgic feeling of adventure is one tinged with guilt and cynicism.

Air travel is really bad for the environment. Really, really bad. According to the UN World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), the tourism sector contributes between 8%-11% of greenhouse emissions of the entire planet each year. The lion’s share of that comes from tourism-related transportation, which is only expected to grow. Outside of transportation, tourism infrastructure such as lodgings, hospitality services, food and drink, and agriculture all take a hefty toll on the planet. However, the WTTC plans to get tourism and travel to net-zero by 2050, which should mean that the average traveler has no reason to worry about changing their behaviors! If that sounds too good to be true, that’s because it is.

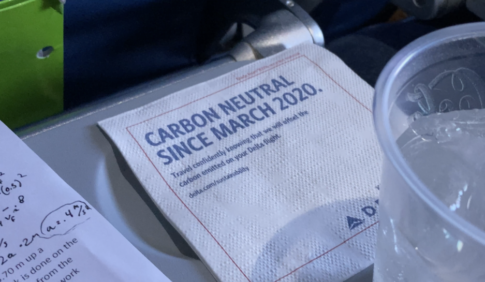

On paper, it’s true that travel is getting less awful for the environment. This is mainly being achieved in two ways, the first of which being decarbonization, or the reduction of existing carbon footprints, such as by introducing new, lower-emissions technologies to replace aging and more unsustainable processes. The other main way that industries reduce their carbon footprint is through carbon offsets, credits that can be purchased by companies or individuals, each representing a ton of CO2 equivalent (CO2e), with the money being sent to fund an environmental project or emerging technology that will prevent that ton of CO2e from entering the atmosphere, or remove it entirely. Together, they seem to make a good pairing for emissions-heavy industries, which can reduce their emissions with decarbonization, and pay for the remainder with carbon offsets. For example, an airline company in the US or EU can use a higher percentage of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) and a newer, more efficient fleet of planes to cut emissions, then cover the rest of their emitted CO2e by funding projects like a solar farm in a global south country or the protection of an area carbon-dense rainforest that otherwise would be logged and turned into cow pasture. Thus, with their emissions canceled out, the company can market their flights as being carbon neutral. However, this only works on paper.

In reality, carbon offsets in their current form mostly benefit the public image and assuage the guilt of the buyer, helping companies with claims of “net zero.” In the above examples, if the solar farm was already going to be built without carbon offset funding, or the forest burns down or is logged regardless of protection, or if the carbon footprint reductions of the projects are counted both by the airline and the government of the country the projects are located in, then the CO2e measurement is completely inaccurate (if it was ever accurate to begin with). Case in point, in 2015 the Stockholm Environment Institute found that three quarters of supposedly carbon mitigating projects following the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which introduced the idea of carbon offsets, did not actually represent any additional reduction to carbon emissions. All of that doesn’t even take into consideration the many human rights violations and other direct environmental impacts such as mine pollution and flooding caused by various “green development” projects which often prioritize the interests of overseas investors above the lives of the real people affected by the project. To summarize, even if an airline provides offsets, or a passenger has paid for an individual offset for their flight, their climate conscience cannot be entirely cleared. Their plane will still emit a dangerous amount of CO2 and other gasses at high altitudes, (this is called radiative forcing, which multiplies the warming effects of emissions) while perhaps flying over a burning rainforest that their offsets helped “save.”

Am I being overly cynical? Probably. Carbon offsets aren’t all bad – they are real projects, many of which can create real positive impact, and they are part of the solution. With a better project success rate and an improved system of accountability/oversight over time from buyers, the system has the possibility to improve and will hopefully be more feasible in the future. For now, genuinely useful projects are definitely worth researching and donating to – but they cannot continue to be an excuse to keep destroying the planet without making changes in other areas. At the moment, carbon offsets can be misused as dangerous tools of greenwashing – creating a misleading image of sustainability without following through on more meaningful action. They also export environmental responsibility from primary sources of emissions to secondary actors, often to lower-to-middle income regions with less historical responsibility for the climate crisis. The system might just need to be re branded in a way that increases transparency and doesn’t imply certainty of full emissions compensation at a one-to-one rate – instead of purchasing “carbon offsets,” perhaps companies and individuals could instead be donating to causes of “carbon optimism.” For the sake of clarity, I will continue to use the disagreeable term “carbon offsets” for this article, or at least until a better name catches on.

For those who see through the greenwashing and give more than net-zero F’s about the environment, is there still a way to travel? Well, sort of. If covering the cost of emitted carbon doesn’t work as advertised, the solution is simply to try to emit as little carbon as possible. The way to do that is to travel closer, and travel slower. Let me explain.

To travel closer is to seek out new experiences in places that may already be familiar by approaching the location with a new, creative mindset. Exploring the place where one lives in new and deeper ways can be just as rewarding (or more) as traveling to parts unknown and having a postcard-worthy, tourist adventure before flying off again. Near my home in Maine, there exists a limitless number of hiking (or ice climbing/skiing, depending on the season) trails to try in the White Mountains that are only an hour away in New Hampshire, plenty of nearby lakes and ponds for me to practice sailing with my friends, campsites to pitch tents at, abandoned mountain logging roads to explore with my brother, and many reasonably close beaches to learn to surf! Even from my front door, there are running routes and bike paths through my small hometown that I have not yet tried. Ironically, I only began to notice how truly endless the adventurous opportunities were at home, just before I left for my gap year in Indonesia, 10,000 miles away.

Despite being quite new to the city of Yogyakarta, having only lived there for one semester, I have been doing my best to explore the area, and I have found the possibilities to be similarly endless. Perhaps the seller that I walk past every day at the market would be willing to teach me how to make my favorite snack, onde-onde (he was!) Or perhaps by surreptitiously walking up to the top of the state oil company-sponsored high rise at the university next-door to the university I take language classes at, I could find a great view of the city (I did!) One can never truly know what opportunities are around them unless they shake things up and try to find adventure in their everyday life and nearby surroundings.

I found this philosophy of traveling close to home through the films of Dr. Beau Miles, an Australian filmmaker and outdoor educator, and author of The Backyard Adventurer, a book that describes his transition from globetrotting glory-seeker, to, well, a backyard adventurer. Acknowledging that straying far from home was bad for the planet, he set himself a challenge of finding new ways to experience everyday settings. From running around his 1 mile block 26 times in 24 hours to complete a marathon while doing as many of his farm chores as possible, to walking his 56 mile commute to work (twice! Once without shoes!!), or kayaking through intensely polluted city waterways to raise awareness about river health, he finds new ways to have adventures right from his doorstep. Adventuring close to home is certainly still adventurous, and definitely better for the planet.

However, the world is simply too big of a place to always stay at home, but in order to continue traveling, we need to change how we do so. I have found that “slower traveling” is more accurate terminology than “sustainable traveling”, because very few forms of accessible long distance travel are truly sustainable. Unless you have access to a Greta Thunberg-esque zero-emissions racing yacht (if anyone does, let’s talk), the options tend to range from more difficult but more sustainable to easier but very unsustainable.

A general rule for understanding transport emissions is how many people a vehicle carries versus the emissions required to move them. The metric typically used is kg CO2e/seat-km. For instance, carpooling is better than driving alone, as more people benefit from the same amount of emissions, therefore each person is responsible for less. This same concept applies to mass transit, because riding a subway with many people splits the emissions among many rather than few. While this does feed into the unhealthy idea of a personal carbon footprint (a cleverly disguised fossil-fuel lobby campaign to make consumers feel responsible for climate change instead of large companies) this math needs to be understood in order to know what type of transportation to choose, not only for personal use, but also to advocate for on a policy level, campaigning with voices, votes, and consumer choices.

Starting with the worst offenders among transportation options, planes and cruises should be avoided where possible. While they both carry a lot of people at once, they both require a tremendous amount of energy to do so. Planes are incredibly convenient due to their speed, but their environmental impact is quite inconvenient for the rest of the world. Conversely, cruises move slowly but luxuriously, with far too many wasteful features like waterslides and casinos that increase their footprint significantly beyond what is needed to move the massive ship from port to port. Better ways to travel by ship do exist, however, such as ferry routes, medium length/overnight liners and by cargo ship, which do not have the associated luxuries of cruises, and are therefore relatively more environmentally friendly (if still quite polluting). Unfortunately, as electric planes are not yet in commercial use, and not everyone can sail across the atlantic ocean, accessible options for sustainable travel by air or sea are currently lacking, so making marginally less harmful choices is really the best that we can do at the moment.

In terms of overland journeys, cars should be avoided unless there are multiple passengers, and not just because road trips alone are not very fun. When driven solo, gasoline cars are quite inefficient, but if carrying two or more people, they tend to be more efficient than planes, if significantly slower. On average, electric cars and EV/gasoline hybrids tend to be much more emissions friendly than gasoline cars. However EVs and hybrids have issues of their own. The production of EVs causes 80% more emissions than comparable gasoline cars mainly due to the energy-intensive and heavily-polluting process of battery manufacturing, and, after the factory, the electricity required to charge an EV or plug-in hybrid can vary significantly in carbon footprint depending on the generation method. Aside from cars, long distance buses are also a very good way to travel on the roads due to lower per-passenger emissions, but by far the most sustainable way to travel overland is by train. While the speed, passenger capacity and emissions are all variable depending on the rolling stock, trains tend to be the best way to travel for the planet, due to relatively high speeds and larger number of passengers. For the adventurous, there are of course, the entirely green overland options of biking long distances, and thru hiking, such as on the Appalachian Trail. While these last methods might be a bit extreme, they could be fun to try, and if anyone has any advice or experience traveling in these ways, please let me know!

While I have many childhood memories of fighting my brother for the privilege of the plane’s window seat, I also have many memories of traveling closer to the ground. In my life, I have been lucky enough to ride with my family on the famed Shinkansen from Tokyo to Kyoto, take intercity rail with some of my best friends from the Rhine to Berlin, and been kicked repeatedly by a random old lady on a crowded night train leaving Bandung, Indonesia. I have been crammed inside a brutally hot ship for three nights crossing the Java sea to Sulawesi, and I have been driven inside a hired van for 18 hours from Bali to Jogja with my bridge year cohort. In 2021, I took a coast-to-coast road trip across the US with my grandmother and aunt in a hybrid Toyota, covering 3000 miles in 5 days, getting opportunities along the route to photograph the Milky Way and to drive through Glacier National Park to see the namesake glaciers before they were gone entirely. I could have reached all of these destinations much faster by taking flights, but I would have missed out on making many good memories with many great people.

Having experiences like these has shown me that flying is not always necessary for travel, and that the pace of a journey can impact both how memorable and how environmentally friendly it is. With slower travel, the destination becomes less important than those that you travel alongside, or meet along the way. When you slow down, the journey itself may become a companion, occasionally giving you a lightning storm at sea or a highway sunrise as validation for the decision to stay close to the ground. Whether you choose to stay within reach of home, or find that your purpose holds to sail beyond the sunset, keep the earth in mind as you do so. Ernest Hemingway, when giving an account of a train and automobile trip with his mortal frenemy, F. Scott Fitzgerald, wrote: “Never go on trips with anyone you do not love.” I love the earth, and I have found her to be the most faithful of traveling companions.

To avoid placing all of the blame for climate change on everyday consumers, as the cartoonishly evil fossil fuel lobby would like, I should give some context. One person traveling more sustainably doesn’t change the total number of flights or cruises taken each day, and one less car on the roads is only one out of over a billion worldwide. However, with enough individuals coming together to create momentum, bigger change can occur. If you are interested in this topic, beyond personal actions as discussed above, consider joining movements in your local area promoting things like cleaner transit, car free streets, and bike infrastructure; voting for candidates who care about environmental issues; and signing up for climate activism groups like the Sunrise Movement or Extinction Rebellion. Much like traveling slowly, change takes effort and time — but it is extremely worthwhile. By keeping close to the ground and pushing steadily towards progress, I am confident that we will be able to reach our destination of a livable planet.

Images:

A bus exits a highway tunnel in New Jersey, November 2021. Kodak TMAX p3200.

Delta Airlines promotes their “carbon neutral” offsetting program on a flight, April 2022

Better traveling practices involve choosing slower alternatives to aircraft and staying closer to home in order to cut greenhouse gas emissions. New Jersey, November 2022. Kodak TMAX p3200.

Ferries and overnight liners tend to be more sustainable than cruise ships or airplanes. Staten Island Ferry, NYC, March 2022. Kodak Ektar 100.

Sources:

https://mediamanager.sei.org/documents/Publications/Climate/SEI-WP-2015-07-JI-lessons-for-carbon-mechs.pdf

https://features.propublica.org/brazil-carbon-offsets/inconvenient-truth-carbon-credits-dont-work-deforestation-redd-acre-cambodia/ https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2015/mar/26/santa-rita-green-dam-killings-indigenous-people-guatemala

https://wttc.org/Portals/0/Documents/Reports/2021/WTTC_Net_Zero_Roadmap.pdf

https://www.euronews.com/travel/2022/05/04/how-do-sustainable-aviation-fuels-work-and-are-they-a-viable-alternative

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1049346/2021-ghg-conversion-factors-methodology.pdf

https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/are-electric-vehicles-definitely-better-climate-gas-powered-cars

Leave a Comment