Jordan: Through the Eyes of An Educator & Student—A Map’s Edge Newsletter Feature

Posted on

01/18/18

Author

JOSHUA EMMOTT & MATTHEW MAGANN

Dragons School Partnership Programs offer much more than an itinerary or the management of ground logistics; In our collaboration with a school, we are dedicated to an aim of fostering a more interconnected, aware, and empathetic student body, faculty, and parent community. The two voices in the following essays speak to the transformative potential that immersive international educational experiences can offer.

Milton in Jordan: Transcending Limitations of the Classroom — A Map’s Edge Newsletter Feature

WORDS JOSHUA EMMOTT

THROUGH THE EYES OF AN EDUCATOR

One of the challenges teaching Middle East history to high school students is how to immerse them in a foreign culture, especially one they only know through the media depictions of war in Iraq and Syria or terrorist attacks in Europe. In our classroom at Milton Academy Massachusetts I have struggled to use texts, videos and Skype interviews with people in the region to move beyond a superficial understanding of culture, gender, religion and how modern day Middle Eastern societies work. Having lived and traveled in the Middle East, I am able to bring personal anecdotes to our studies. But I have felt that even though my students can converse intelligently about the politics and history of the region, they still leave my class feeling that Islam and Muslim culture are opaque and impenetrable topics that they do not really understand, and so they are left with little understanding of the diverse voices that are active and vibrant in the region.

This frustration and inability to provide students with a holistic understanding of the Middle East led me to explore alternative ways to connect my classroom to the Middle East. This is how I found myself in Madaba, Jordan in March 2016 with nine other American teachers learning about experiential education for the first time. Having been a Peace Corps volunteer in Jordan and having traveled extensively in the region, I thought I knew everything there was to know about Jordan, only to discover that I was quite mistaken.

In March 2017, I returned to Jordan with eight of my Milton Academy students for a ten-day cultural immersion into Jordanian society. None of my students had traveled to the Middle East before and one of them had never left the United States. From the moment we stepped out of the Queen Alia Airport into the hot desert air until our return home ten days later, all of our assumptions about what Jordan represented, who we were, and what it meant to be a citizen of the world were constantly being challenged, tested and affirmed.

Our Dragons partnership course was deliberately designed to take everyone out of their comfort zone and provide time for each member of the group to process at their own pace. In Amman, my students would gather every night on the rooftop terrace of our hotel to passionately discuss and debate for hours the impact of the Syrian refugee crisis on the stability of Jordan; what it means to be Jordanian; the role of Islam in Jordanian society; whether the tribal structure is a force for regime stability or an obstacle to democratic reform; and how to understand the role of women in Jordan. Questions abound in the moment, but for some, our ten days in Jordan also resulted in an overwhelming encounter with ‘the world’ that left them still processing the experience weeks after we had returned to Milton.

To start our exploration of Jordanian culture and gender, our group was invited to lunch by a remarkable woman named Khaloud. The students and I spent an entire afternoon in Khaloud’s apartment with her two college-aged children and her elderly parents. Over the course of an hours-long feast, the students practiced their recently-acquired Arabic language skills; learned what it was like to be a young women studying science at a Jordanian college; and from Khaloud’s father, what it is like to be a Palestinian who lived in Saudi Arabia and now resided with his divorced daughter in Amman, Jordan. In our discussions over a mountain of kebabs, bread and grilled vegetables, the students shared their family stories and the role of elderly family members in their lives. We were all challenged to think about how the elderly are treated in the United States versus the Jordanian approach of having your elders move into your house when they become too frail to live on their own.

After tea was poured—a sweet, sugary, aromatic mint tea that is the mainstay of all social interactions in Jordan—we all gathered around the family table while Khaloud shared her life story with us. Khaloud’s father arranged for Khaloud to be married to a Saudi man twenty years her senior when she was a young teenager. After her second child, Khaloud resolved that she was going to challenge the patriarchal structure of Saudi Arabia and run away to Jordan to get divorced, as there exists no such option to escape an oppressive marriage for a woman in Saudi Arabia. Khaloud then shared her story of building a new life in Jordan, and how difficult it is to be a divorced woman in a society where marriage is the norm. This powerful and personal experience of sitting in Khaloud’s apartment with her family as she shared her life story raised more questions than answers. After two hours listening intently to Khaloud’s story, the students paid respects to the family and we departed. We regrouped at Al Jadal café in Amman to digest and process Khaloud’s journey and better understand what this revealed about the role of women in Jordanian society.

The power of our Dragon’s course in Jordan was that we never knew where the conversation was going to take us. Our visit to Al Jadal was meant to be a fun break from the heady discussions of the morning and an opportunity to learn the debkhe (traditional Jordanian dance). For over an hour, our group tried to follow the lead of our female instructor as we attempted to replicate the debkhe, which looks like a simple line dance, yet is deceptively complicated. After an hour of going right instead of left, we took a break to have a traditional Jordanian dinner cooked by Syrian refugee women working with an NGO associated with Al Jadal. After dinner the owner of Al Jadal sat down for tea and explained how his café was opened after the Arab Spring as a forum to debate the future of Jordanian politics and society. During our discussions, one of my students asked the owner of the café to explain an aside that he had made about the role of Islam in Jordanian society. Our discussion of politics suddenly took a turn and we found ourselves challenged to think about what the role of religion should be in society. Moreover, we were challenged to consider our individual role in creating a more equitable society. When should one engage in political protest or support the status quo? Is democracy the best form of government?

This unexpected turn in our dinner discussion led to another late night on the rooftop of our hotel as my students developed a reading list of books they planned to read post-trip in order to better understand what was possible if one wanted to create a better world.

From Amman, we crammed into a small Jordanian bus and traveled south to Wadi Rum and our four-day homestay in the desert town of ad-Disah. This was the first time we had left Amman and traveled into rural, conservative Jordan. After four hours driving passed flat sandy expanses, highway rest stops, and small settlements with twenty houses surrounded by endless brown landscape we passed through ad-Disah in the dark and arrived at Salah’s Bedouin camp at the entrance to Wadi Rum. Stepping out of our small bus into the darkness and silence of the desert, surrounded by the stone cliff formations of Wadi Rum, my group fell silent and nearly paralyzed in awe of the lunar-like surrounding where we would be spending the night. Sitting on the floor of the Bedouin tent we were treated to a traditional feast. As we ate, we again engaged in a discussion with our host Salah, this time on the role of tourism in Jordan and its impact on traditional Bedouin societies like that of ad-Disah, where each of us would live with a host family for the following four days.

As we ate breakfast at Salah’s camp, the group was noticeably quiet and visibly nervous about the prospect of living alone with an unknown family in an unknown place. During our debrief before the homestay it was clear that everyone was very apprehensive about how they would spend four days with a family that did not speak English: How would they know what to do? How would they know what the cultural cues were? What if someone made a cultural faux pas?

Our two Dragons leaders, Cate Brown and Elley Cannon explained how the homestay would work and patiently answered everyone’s questions. When the clock struck 10AM we all piled into the back of a pickup truck and headed into ad-Disah to drop the students off at their new home for the next four days. The truck ride into ad-Disah was the quietest I have ever seen my students.

After a night in our homestays, we all congregated in the diwan (living room) of my host family’s house and debriefed our first twenty-four hours in ad-Disah. Two of the boys arrived in traditional Bedouin dress as their host families had taken them shopping in town. The two girls in our group were dressed in traditional Bedouin dress of head scarves and long robes as within this conservative society the female dress code is prerequisite for an immersive homestay experience. Right away it was clear that some of the students were having a great time and were forming bonds with their host families, and that there were other students who were completely overwhelmed, questioning whether they could spend another day in ad-Disah. The two female students in our group were struggling with the gender roles and how to reconcile their personal views with communal norms of ad-Disah.

On day two of our homestay there was a wedding in the village, which created a lot of excitement among the students. Jordanian weddings are multi-day affairs where men and women celebrate in separate locations. For the men, the weddings are all-day affairs in which they sit under long tents and drink rounds of tea and discuss family and politics for hours on end. For my students, sitting for hours with a limited ability to speak Arabic, and having to politely drink dozens of cups of sugary tea, not understanding what the hundreds of men in the tent were discussing, turned into an endurance contest and a real challenge to embrace a way of life that moves at a glacial pace compared to Milton. During one of our many discussions under the tent, the students observed that all of the younger men in ad- Disah had cellphones and spent hours upon hours transfixed by the screens. This ultimately led the students to start discussing the role that cellphones played in their own lives, and how the absence of a cellphone in Jordan had made them rethink the role that technology plays in their lives back at Milton. Transference, in a way, had begun.

Our last night in Jordan was a magical evening spent out in the middle of Wadi Rum sitting in a circle under the stars discussing ways in which we could bring our experience in Jordan back to Milton. As it turned out, one of the female students in our group, Mollie, spent her final month of school volunteering at a local mosque helping with Ramadan preparations and furthering her understanding of Islam. One of the six boys in our group, Matt, returned to Jordan this past summer to teach English at a local school in Zarqa in far eastern Jordan. The rest of the students have all expressed a sincere desire to pursue Arabic and Middle East History this fall as they start college.

The most fulfilling part of this experience for me was during our final night in Jordan, as I sat under a blanket of stars in Wadi Rum listening to each member of the group articulate the ways in which he or she had been challenged on this course and the ways in which they had grown both as a person and in their understanding of Jordan. Back at Milton, in our final month of the course, I took immense satisfaction in listening to the eight students who went to Jordan help their peers to better understand the cultural complexity of the kingdom. My goal is to bring my entire Middle East History class to Jordan every March. The impact of this trip on their understanding of local culture and society proved that experiential education is not only measurable, it is transformative.

JOSHUA EMMOTT was a participant on Dragons 2016 Jordan Educator course. Following the Educator Course, Joshua helped formalize the first Dragons-Milton Partnership Course in Jordan the spring of 2017. He and his students are headed back to Jordan with Dragons again in 2018. Joshua first traveled to Jordan in 1997 as a member of Peace Corps. Later, he and his wife Anne started a business importing olive oil soap from Syria and carpets and jewelry from Yemen and Pakistan. Since 2003, Josh has lived and taught Middle East History at Milton Academy.

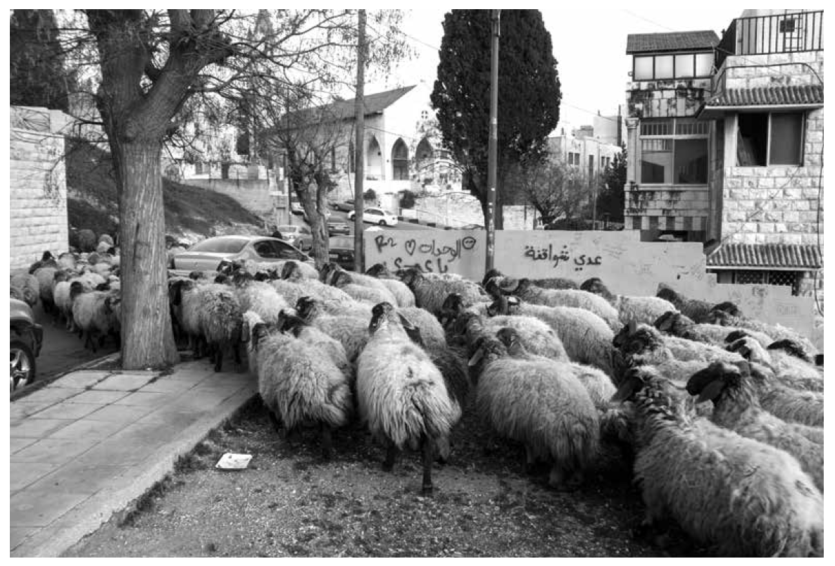

Herds of sheep coexist with

upscale apartments and embassies in Jebel Amman, a neighborhood of the capital.

Milton in Jordan: Discovering the Middle East — A Map’s Edge Newsletter Feature

WORDS & IMAGES MATTHEW MAGANN

THROUGH THE EYES OF A STUDENT

“ISN’T IT DANGEROUS?” That’s the main question I heard when I told people I was traveling to Jordan. By and large, the West’s conception of the Middle East centers around terror, and mentioning the region calls to mind the horrors of September 11th and Islamic State.

That isn’t the picture I got in Jordan. Fear never crossed my mind as I walked through the bustling alleyways of Amman. A mixture of people, shops and traffic filled the streets of the capital city, whose electronics vendors and cafés melded together with ancient souks and Roman ruins. I witnessed a dynamic and rapidly changing society, albeit one deeply impacted by regional events. Massive, repeated inflows of refugees have heavily taxed Jordan’s limited natural resources. Despite that, it remains a stable and vibrant nation, one of the most successful in the Middle East.

I spent ten days this past March in Jordan as part of a Dragons Partnership program with my high school, Milton Academy. We flew into Amman, where we stayed for a few days before driving down to ad-Disah, a Bedouin village in the southern deserts near Saudi Arabia. Although I had studied the Middle East both in class and independently, I had never left the Western world before and little prepared me for the experience I had in Jordan. I saw scars borne of the conflict and turmoil that continues to plague the region, but I also found an audacity and an authenticity unlike anything I had previously experienced.

As a tall, white, blue-eyed American, I clearly stood out on the streets of Amman. So I quickly learned that in Jordan nearly everyone bids you welcome. Whether alone or with our student group, people would spontaneously call out “Hello!” in English or “Ahlaan wa sahlaan!” (welcome) in Arabic. In possession of only the name of a restaurant and the Jordanian Arabic term wa’in (where), I managed to navigate through the labyrinth of Amman’s streets, each person I asked immediately pointing out the next few turns like a personal guide.

I spent the most time immersed in Jordanian culture while staying with a Bedouin host family. They spoke little English, and I no Arabic, yet I felt immediately welcomed into their home. The children in my family weren’t quite sure why I didn’t understand Arabic, but they took me around the village, introducing me to their friends and cousins and inviting me to play soccer. For a region so often stigmatized as hostile and violent towards the West, I found Jordan unusually friendly and welcoming. I certainly met Jordanians who held political disagreements with America, but I never felt those tensions shifted onto me as an individual. Perhaps in a region where states are often artificial and leaders frequently lack the popular mandate, separating the individual from the nation comes more naturally. Or, as I suspect, the welcoming culture I experienced in Jordan extends to everyone, regardless of language or nation.

Although the Middle East may not fit the violent stereotypes of the West, it has undoubtedly suffered through some of the worst atrocities of modern times. Jordan, despite its own stability, has had to deal with the impacts of the conflicts surrounding it. Most of the population is not native Jordanian. A majority have Palestinian ancestry, and the recent conflict in Syria has brought in nearly 1.5 million new refugees. A massive influx of Palestinians arrived in the wake of the 1948 war, and with some obstacles, Jordan has managed to successfully integrate them into society. The current Queen Rania of Jordan is Palestinian-Jordanian, for example. Unlike neighboring Lebanon, Palestinian refugees and their descendants can adopt Jordanian citizenship. Issues still exist surrounding Palestinian-Jordanians, but considering the sheer number of people involved, Jordan has had remarkable success in integrating refugees. In recent years, the Syrian refugee crisis has presented a new challenge. I met with multiple NGO workers helping the Palestinian-Jordanians, but considering the sheer number of people involved, Jordan has had remarkable success in integrating refugees.

In recent years, the Syrian refugee crisis has presented a new challenge. I met with multiple NGO workers helping the Jordanian government to handle Syrian refugees. The refugees have created tension within Jordan, which accepted them on the premise that they would return to Syria at the close of the conflict. Unfortunately, the current situation does not lend itself to any sort of peaceful resolution. The tide of the war seems to have turned in Assad’s favor. While some refugees would contemplate returning to a state under his rule, for those refugees who had any involvement with the opposition return could mean death. The mass migration of Syrians has put a strain on Jordan’s social services, and many Jordanians dislike the prospect of permanently settling refugees in Jordan. Although the government welcomes material aid, relief agencies often come up against opposition when they try to integrate refugees into society.

Like many others, I had read about the crisis in the Mediterranean and the controversies surrounding Syrian refugees, but the issue still seemed distant and detached from my experience. Visiting Jordan and speaking with both refugees and those helping them gave me a better grasp of the problem. It also humanized the crisis for me. These people were not faceless, helpless masses nor were they fanatical Islamists determined to bring down America. They were people not very different from myself.

I met one man who had been a lawyer in Deraa, a rebel-occupied city in southern Syria and the scene of intense fighting. His life had not been that different from my own. He studied at the university and lived a comfortable life with his family. Then one day his home was bombed by Assad’s forces and he was forced to flee across the border to Jordan, where he now lives as a refugee, separated from his wife and children. Despite that, he volunteers his time helping less fortunate Syrians adapt to life in Jordan. His audacity in continuing to advocate for refugees was not unusual. I spoke with a woman who had fled an abusive arranged marriage, risking her life to do so. I met one young man who did not believe in god, putting his social standing and even his life in danger in order to stand for what he believed in. Even on a small level, I saw acts of courage, like the young Bedouin father who bottle-fed his baby son, cutting against traditional gender roles. We often rationalize the suffering of those in other cultures as divorced from our own reality, as not our issue. Spending time in Jordan broke down those barriers of culture and geography, revealing to me how fundamentally familiar and how fundamentally human the seemingly distant Arab world is.

I still haven’t quite processed my time in Jordan. It’s been eight months now, but I still think about my time there. I’m now beginning college, and I’ve decided to study Arabic this year. I hope to return back to Jordan, perhaps this summer, to build on the experience I had. Something about the streets of Amman, with their traffic and little DVD stands and restaurants and car horns and the smell of tobacco and the long nights spent up on rooftop balconies talking through meaning and purpose and direction, impacted me deeply. My time in Jordan drastically changed the way I think, and it continues to challenge me, both as an individual and as a citizen of the planet.

MATTHEW MAGANN attended a 2016 Dragons Partnership program with Milton Academy in Jordan. Originally from the Boston area, he currently studies at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he is a writer for The Dartmouth and an active member of the Dartmouth Outing Club. He also works at the Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory in Milton, MA, has volunteered at a number of archaeological digs, and has recently begun work at a Dartmouth ice core lab.

This article was featured in the Winter 2018 Edition of Dragons bi-annual Newsletter, The Map’s Edge. Each newsletter explores perspectives from Dragons community through the voices of our Alumni, Instructors, Partners, Parents and our International Staff and contacts. Feel free to view our archive of editions of The Map’s Edge or even submit a piece to be featured in our next issue by sending an email to [email protected].

Leave a Comment